Possession, Feminism and Bodily Autonomy in Horror

Reyna Ledet is a 2022 UT Grad who majored in Geography and Religious Studies. She enjoys analyzing the ways religion interacts with modern life, and the ways humans use stories to better understand themselves. This past semester, she took AMS311s “Haunting in American Culture.”

Fears of women’s bodily autonomy have fueled American moral panics for decades. The right of a woman to divorce, control her own money, and even to express her femininity has been controlled and limited over time. Even now, in 2022, the imminent overturn of Roe v. Wade promises to hurt women across America. However, issues of bodily autonomy are not the same between white women and women of color. Women of color and disabled women have historically faced forced sterilization on top of forced births, and Black women in America face an alarmingly high maternal mortality rate[1]. In media, confronting these issues directly can be difficult or painful; sometimes, framing this stolen control and the resulting trauma as supernatural can make catharsis over the issue more accessible. Possession in media often acts as a metaphor for the ways men violate and claim ownership of women’s bodies, but depending on how the narrative treats the possession, it can also indicate something about the politics the creators subscribe to - intentionally or not.

The two sources used here to illustrate this point are Jennifer’s Body, directed by Karyn Kusama and written by Diablo Cody, and Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia. Both sources are pieces of pop culture, and both involve women at high levels of creative control. Neither source involves the straightforward narrative of possession (a ghost taking over a body and using it to act on the material world), but both invoke possession as part of their narrative. Both sources also rely on genre to help tell their stories; Jennifer’s Body with the rape/revenge genre, and Mexican Gothic with gothic and cosmic horror. Each story plays with genre and references wider social forces, but ultimately, one story more successfully presents a nuanced understanding of bodily autonomy, and the comparison reveals the limits of a mostly white feminist perspective.

Jennifer’s Body uses possession to imply a sexual assault, and its muddled message tries to create an empowerment narrative by refreshing the rape/revenge genre. In the movie, an indie band called Low Shoulder sacrifices a high schooler named Jennifer to Satan to gain fame and influence. Because Jennifer is not a virgin, she dies and transforms into a succubus who feeds on people to survive. The movie frames the circumstances around Jennifer’s kidnapping and sacrifice sexually – she claims to be a virgin in the van on the way to the Devil’s Kettle to convince the band not to rape her, the band sings the song “8675-309/Jenny” by Tommy Tutone (including the line “I used my imagination, but I was disturbed”)[2] as the frontman of the band stabs Jennifer repeatedly in the stomach, and after the assault, he stands and breathes heavily as if he has just climaxed. Despite not directly depicting a sexual assault, the framing of the situation conveys the same effect. This assault transforms Jennifer into a demon, and she loses her empathy and begins to terrorize the town. The band gets to be the town heroes for most of the movie while Jennifer becomes the villain; only Jennifer’s guilt-riddled friend Needy understands the truth of the situation. The choice to use an indie band to commit this crime calls to mind the ways the alternative music scene preyed on young female fans in the 2000s[3]; it speaks to an awareness of broader social forces that might make a young woman vulnerable to attack. There is no doubt that the reason for Jennifer’s possession is meant to be a metaphor for a sexual violation of a woman’s body, but her atypical reaction to the trauma allows her to begin a revenge narrative that serves the audience on a shallow level.

The film tries to revamp the “rape/revenge” genre of films – movies in which a woman is sexually assaulted, and then someone seeks revenge for this transgression – but it undermines its message by clearly depicting Jennifer’s actions as evil. Jennifer’s Body follows the structure of a rape/revenge story, but it was created for teenage girls and reflected what teenage girls in 2009 might have needed to see in a horror movie.[4] While movies that depict women seeking their own revenge on their assaulter (such as I Spit on Your Grave) already exist, Jennifer’s Body spends less voyeuristic time on the assault and more time on Jennifer’s reaction to the trauma. [5]

“Jennifer’s Body and the Horrific Female Gaze” discusses how the movie does not reveal the actresses’ bodies to the audience, allowing them to retain their dignity;[6] many rape/revenge stories include a exploitative depiction of the rape to either titillate or horrify the audience. Watching Jennifer tear apart men who see her as sexually desirable without ever showing actresses nude may feel good to audiences who deal with misogyny and unwanted sexualization. However, despite being visually empowering, the message becomes more confused in the text of the movie.

Jennifer begins to consume young men that find her sexually enticing, including Needy’s friend from class, Colin, and Needy’s boyfriend, Chip. One of the themes Diablo Cody wanted to explore in her writing was the complex dynamics of high school female friendships[7], which explains why the film centers Needy and Jennifer’s relationship. However, the emphasis on the complexity of teenage girls creates problems for the attempt at an empowering rape/revenge format. Jennifer’s first victim lacks a support network in America, her second is grieving the loss of a friend, her third was just a young man with a crush, and her fourth had just gone through a confusing breakup with his girlfriend. None of these boys indicate a desire to violate Jennifer; to their knowledge, Jennifer consented to their sexual encounters. In the same way that Low Shoulder took advantage of Jennifer’s vulnerability, all of Jennifer’s victims had vulnerabilities she exploited to violate their bodies. At least one person in the community grieves each murder victim, some very intensely. While visually and out of context, Jennifer’s sexualized murders may feel like empowering revenge, the cruelty of her murders steals any empowerment audiences might get out of the movie. Jennifer’s demonic callousness puts her in conflict with Needy, which is more relevant to the plot than the fact that Jennifer was assaulted. For instance, Jennifer chooses to kill Colin because Needy expressed fondness for him, not because he deserved death (according to the movie’s moral code). Jennifer does not even get to enact real revenge by killing Low Shoulder; Needy kills the band with the demonic powers Jennifer inadvertently gave her. The focus on Needy’s journey reduces Jennifer to a sympathetic villain whose tragic loss serves as motivation for another character’s narrative. The subversions in genre the film succeeds at do not refresh the rape/revenge genre; they only create new thematic problems.

The movie also has problems with race. When asking if Needy and her boyfriend have just had sex, Jennifer asks if they have been eating “Thai food”[8]. Ahmet, Jennifer’s first victim, never speaks, only communicates in nods and head shakes. Jennifer also tells Needy to get her nails done by a woman who is Chinese[9] after seeing how damaged they got after Needy cleaned up Jennifer’s vomit. These “edgy” elements alienate Asian viewers, despite the creators’ desire to represent teenage girls as a population. Beyond the specific problematic elements, there are also structural issues with the narrative that further a white feminist perspective. If the creators intended to write Jennifer’s character as a power fantasy that punishes evil men, then she represents a fantasy wherein the predator is replaced rather than removed. In the same way that hiring more female CEOs will not solve the problems women on the whole face under capitalism, shifting an unfair power dynamic to include women still perpetuates the power dynamic. Modern audiences resonate with the queerness depicted in the film[10], but the positive representation does not erase the problems. Despite subverting some expectations, Jennifer’s Body does not address the issues its possession metaphor brings up and fails to consider broader societal ills that can amplify or change the implications of a sexual assault.

In contrast to the lack of consideration for race and other systems of oppression in Jennifer’s Body, the novel Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia uses possession as a metaphor for the long-lasting impacts of colonialism on Mexican women’s bodies, as well as how misogyny affects the colonizers and colonized in slightly different ways. The patriarch of the Doyle family, Howard, forces Noemi to consume mushroom spores by kissing her. This violation of Noemi's body turns her into an asset to the Doyle family by trapping her within the family manor. While there is no true ghostly possession, the mushrooms still exert influence over the bodies of the people of the house, so they act as a possessing force the same as any ghost. Notably, though, the mushroom spores exist as a part of the Mexican landscape that is exploited by outsiders. In the section of the Book Club Guide titled “A Letter from the Author,” Moreno-Garcia discusses the exploitation of indigenous people by mining operations.[11] Repeatedly, foreign powers forced locals to work the land only to steal from the Mexican landscape for the benefit of European empire. These exploitations displaced Indigenous people and killed many others. Howard Doyle turns the mushrooms into a method of profit and prolonged life, like the mineral deposits mined by Europeans, while actual Mexicans wither away. Only a select few Mexican people, such as Noemi, are allowed into the gene pool of the family to keep it from becoming too poisoned by incest, just as colonizers might marry an indigenous woman despite disrespecting their land, traditions, and autonomy. The Gloom of the mushrooms calls to mind the ways the haze of colonialism lingers over Mexico and its people - by stealing from and ruining the landscape, by traumatizing Mexican women over hundreds of years, and by allowing Mexican families to be torn apart by diseases. Howard’s dependence on the Gloom ties into this metaphor by positioning him as the colonizing parasite that sucks away the vibrance and resources of the indigenous community. The possession in this case has its sexual element - Noemi is expected to reproduce heirs to the Doyle family for Howard to possess in turn - but it also involves the inherent racism of the situation. Noemi and Catalina are not the only women in the book, though; Howards’s exploitation of his own family reveals the ways white women use power but still face oppression by white men.

Howard uses both Florence and Agnes Doyle to further his goals, but both women cause harm to Noemi and the Mexican people in the nearby village despite their own abuse. Florence acts as an antagonist throughout the novel by criticizing and belittling Noemi. When Noemi tries to escape with her cousin, Florence attempts to kill Noemi. Clearly, Moreno-Garcia did not intend to make the reader like Flroence, though there are glimpses of her humanity. She wanted to escape many years ago, clearly feels unhappy about her husband’s death, and the fruits of her labor are used by Howard the same as anyone else’s. Ultimately though, she serves the system she was forced into by Howard by participating in the conspiracy to trap Noemi. Florence inspires the audience to consider how she fits into a broader hierarchy in the narrative – she buys into Howard’s ideas through a combination of abuse and a sense of superiority. Howard treated Agnes in much the same way, only more egregiously. Agnes’ body is possessed by the mushrooms more thoroughly, but she in turn possesses the house and the people within it. Howard’s demands, expressed via the mushrooms, have nearly completely replaced her, and her only options are to beg for freedom and lash out. Like Jennifer in Jennifer’s Body, Agnes’ trauma transforms her into something monstrous, but her monstrosity is never mistaken for empowerment. “What had once been Agnes had become the gloom;”[12] Agnes’ perpetuation of colonial systems of power hurts her as much (if not more) as it hurts everyone else. Howard Doyle possesses the bodies of Agnes, Florence, and Noemi, but Agnes and Florence try to claim their own power by helping Howard. The unbalanced power dynamics empower no one, and only destroying the entire system can free the inhabitants of the house.

Like Jennifer’s Body, Mexican Gothic plays with genre to make points about the genres’ treatment of women. In contrast though, Mexican Gothic also has things to say about the ways oppressive power structures affect participants, even privileged ones. The “Gothic” in the title indicates that Moreno-Garcia intends to explore genre. For instance, the name “Howard Doyle” is a combination of H.P. Lovecraft and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, two giants in the realm of cosmic horror and mystery, respectively. Moreno-Garcia writes in the Q&A section of the Book Club Guide that “several of their stories contain racist elements”[13] (something of an understatement in Lovecraft’s case), nodding to the fact that while these genres are powerful and compelling to readers of many different kinds, oppressive elements exist in the foundations of these genres. In “The Girl in the Mansion,” Moreno-Garcia discusses the genre tropes that make up the building blocks of a mid-century “gothic” novel. The “formula” she discusses includes “a young woman, a big house, and a dangerous yet exciting man.”[14] The dangerous man in this case is Virgil, Catalina’s husband. In the vein of Byronic, gothic heroes like Rochester and Heathcliff, Virgil plays the role of a misunderstood man to fool Noemi into compliance. Virgil uses the Gloom to molest Noemi several times throughout the novel, but the reader understands the horrified sexual arousal Noemi experiences as the confused sexual arousal Gothic love interests of the past inspire in the heroines of old. When the story confirms that Virgil manipulated Noemi, the reader must confront the idea that the abuses excused by Gothic stories of the past are truly just abuses. Virgil represents an extension of postcolonial thinking that disguises itself as harmless or charming.

Francis Doyle is the sort of man who could be the protagonist of a cosmic horror story, but his subversive treatment by the narrative allows him the freedom to escape the horror. In his video “Outsiders: How to Adapt Lovecraft In the 21st Century,” Harris Brewis discusses the reasons that Lovecraft’s writing may resonate with queer viewers despite Lovecraft’s noted homophobia and extreme racism. One of the things that Brewis discusses is the way that Lovecraft gestures at the feeling of facing down an uncaring god[15]; the Doyles refer to Howard as a god repeatedly, and Francis’ family expects him to become Howard’s new host body (thus also indicating the ways that oppressive power structures violate the bodies of men). More broadly though, Brewis discusses the ways that Lovecraft expresses the feeling of being an outsider to a society that does not understand you. Oppressed people of many backgrounds feel the anxieties of existing in a world that actively does not care for your needs. Francis must exist with the knowledge of the horrors his family has committed even as they treat him without respect. Only when Noemi exhibits the strength to overthrow the order of the world as it stands can Francis emerge from the shadow of guilt over the actions of his family. As a white person, Francis must assist in the fight against the remaining issues of colonialism and imperialism, despite whatever difficulty he has in grappling with his feelings. The relationship between Noemi and Francis indicates another departure from genre; in cosmic horror of the Lovecraft variety, characters usually react to knowledge by going mad. Noemi, as a woman of color, gets to have a happy ending where she gets to navigate her trauma with two allies (her cousin and Francis). Brewis discusses The Shape of Water, directed by Guillermo del Toro, as a way Lovecraft can be adapted for a modern audience. He argues that allowing the monster humanity through its interactions with the minority characters represents a better way to approach the horror of the outsider – from the outsider’s perspective.[16] Noemi and Francis are both outsiders to the world of the Doyles, and their differences in power give them different strengths and weaknesses when fighting the evils of the Doyle family. In cosmic horror stories, happy endings represent a radical idea for outsider (or minority) characters, and Mexican Gothic stands as a more empowering story because of the choice to have Francis and Noemi make it out together.

Jennifer’s Body and Mexican Gothic both have things to say about the horror of a violation of bodily autonomy, and both have elements that work thematically in their favor. However, where Jennifer’s Body fails to express a coherent theme, Mexican Gothic considers the ways social forces combine to create a worse outcome for some women than others and recognizes where a system should be taken apart instead of reassessed. The “possessions” in their narratives both discuss the ways men take advantage of women, but “possession” inevitably means something different to a white woman and a woman of color based on their respective histories in the world. Also, Mexican Gothic understands the ways that men can be preyed upon too, while Jennifer’s Body unintentionally revels in the idea. Overall, to really understand issues of autonomy, pop culture should center compassionate and intersectional feminist works.

[1] Donna L. Hoyert, Ph.D, "Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last modified February 23, 2022, accessed May 8, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/maternal-mortality-rates-2020.htm. The statistics referenced are from 2020, where the maternal mortality rate for Black women was 55.3%. This data fluctuates heavily due to the relatively small number of maternal deaths yearly, but even in the two previous years, Black women had the highest rate among White, Hispanic, and Black women.

[2] Jennifer's Body, directed by Karyn Kusama, screenplay by Diablo Cody, 20th Century Fox, 2009.

[3] Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen, "How the pop punk scene became a hunting ground for sexual misconduct," The Brag, last modified November 23, 2017, accessed May 8, 2022, https://thebrag.com/pop-punk-internalised-misogyny-brand-new/.

[4] "Jennifer's Body & the Horror of Bad Marketing," video, 20:06, YouTube, posted by Yhara Zayd, June 1, 2020, accessed May 6, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=llQ_OpOl7Qg&list=LL&index=8.

[5] Cinemagic Pictures, I Spit on Your Grave Poster, image, JPG. Theatrical release poster for the film I Spit on Your Grave. This image centers the sexual appeal of the main character, despite the condemnation of the assault she faces in the movie. The marketing for Jennifer’s Body looked much the same, but the marketing undermined the message of the movie, as argued by Yhara Zayd in her video on the topic (cited elsewhere).

[6] "Jennifer's Body and the Horrific Female Gaze," video, 20:34, Youtube, posted by The Take, July 27, 2021, accessed May 6, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X7Twg8rG2HI&t=221s.

[7] "Jennifer's Body & the Horror of Bad Marketing," video.

[8] Jennifer's Body.

[9] Jennifer's Body.

[10] "Jennifer's Body & the Horror of Bad Marketing," video.

[11] Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Mexican Gothic, book club edition. ed. (New York: Del Rey, 2021), 307.

[12] Moreno-Garcia, Mexican Gothic, 284.

[13] Moreno-Garcia, Mexican Gothic, 313.

[14] Moreno-Garcia, Mexican Gothic, 318.

[15] Outsiders: How to Adapt H.P. Lovecraft in the 21st Century, screenplay and performed by Harris Brewis, 2018, accessed May 8, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l8u8wZ0WvxI.

[16] Outsiders: How to Adapt H.P. Lovecraft in the 21st Century.

Honoring our AMS Senior Thesis Writers

Next Friday, May 6th, the American Studies Senior Thesis writers will be presenting their work. To honor their accomplishments, we are publishing short interviews with each. First up is Jordan Maxwell, an American Studies major graduating in December! Congrats Jordan! Interview by Holly Genovese

HG First up, what is your thesis title and what is it about?

JM: The title is “Disability as an Identity: The Social Construction of Lupus in American Society.” I conducted research on the autoimmune disease, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, to illuminate the lack of attention and misconceptions society has regarding not only the disease itself, but disabilities as whole in American society. Building a social construct of lupus allowed me to observe, analyze, and synthesize how the interactions of individuals created a reality based on shared assumptions in order to make sense of the objective world. These findings were further enhanced by my evidence concerning disability studies in the United States, as it explains why disability is an identity.

HG: How were you introduced to the topic or subject of your research?

JM: I was diagnosed with lupus when I was 11 years old and it has changed my life significantly. I had always wanted to do more research regarding lupus and this seemed like the perfect opportunity to do so.

HG: How did American Studies influence your research trajectory?

JM: American studies influenced my trajectory because I was able to tie in a social aspect that I couldn't see before. Building a social construction involved having conversations with individuals in society, analyzing statistics, synthesizing historical resources, and understanding the behavior of society when it comes to these topics. Focusing primarily on lupus gave me insight to many characteristics of the disease, but putting lupus under the scope of a disability allowed me to dive into and compare it to disability studies in the United States.

HG: Were there any courses, inside or outside the department, that were particularly influential? Even if not directly related to your topic?

JM: A course that significantly influenced my research was my UGS course I took freshman year. Taught by Dr. James Patton, Disabilities in the Media was my first step into the disability world. Even now, if people ask me what my favorite course at UT has been, it remains to be this one. This course allowed me to understand disabilities in society through culture, society, and politics rather than through a medical perspective, which is what I was used to. On a side note, I believe this helped me to declare my major in American Studies because I realized I had a passion for learning about culture, history, and social sciences

HG: If it's not too annoying of a question, what's next? Or what do you hope to be next?

JM: What's next is definitely a big question. I started writing this thesis last fall whenever I was a junior and didn't have the greatest sense of direction in my life. With a clearer path now, I plan to graduate in December and take some time off before continuing on to either graduate school or law school. Writing a Senior Thesis as a junior was definitely stressful and added more work to my plate than I was initially prepared for, but I'm grateful for what it has taught and shown me throughout the past year.

HG: Do you have any fun summer/celebratory plans?

JM: Although I still have some time before I graduate, I do plan to study abroad in Vienna, Austria this summer! I've never traveled abroad before so I am excited for the opportunity to explore a different city/country while learning about the society and culture

The Benefits of Expanded Academia

Dr. Randy Lewis, Professor and Chair of American Studies

You’ve probably heard of expanded consciousness but have you heard of expanded academia? It’s less trippy but still pretty valuable— and it’s legal in the state of Texas!

Let me explain.

Last week Dr. Rebecca Peabody (Getty Museum) met with a few grad students in American Studies and History for a wonderful conversation about what she calls “expanded academia,” her phrase for the broader landscape of academic and quasi-academic jobs that exist beyond the tenure track paradigm.

I suspect that the room was filled with people who are trying to figure out if typical academic jobs make sense for them. Fortunately, Dr. Peabody had a lot of good advice. She encouraged us to recognize how many choices we can have if we are willing to work within a larger ecosystem.

Indeed, what I took away from her talk was how much agency we are leaving on the table when we decide to say “nothing matters except that tenure track job—I’ll take it no matter what the cost!” That sort of academic tunnel vision can limit our sense of what is possible with our PhD.

Where does that tunnel vision come from? Increasingly it’s not coming from faculty; for instance, our department has an incredible record of placing people in expanded academia over the past 40 years and has been immensely celebratory of all of the various outcomes. We have never valorized one outcome over another but perhaps the phrasing is part of the problem now; there is something odd about the expression “alt-ac” because, as Dr. Peabody points out, few people are “in or alt” in some simplistic either/or way. For most PhD’s, the career path is more serpentine than straight line.

After all, graduate work in American Studies can prepare us for positions in administration, advising, curation, journalism, and other fields. For this reason Dr. Peabody talked about the importance of “same preparation, multiple outcomes” rather than “preparing for one outcome.” She suggested that academic skills are very transferable—even more so than we expect. She also talked movingly about “iterative self-discovery as an important life skill” and how your feelings of self-doubt along the way are not a sign of weakness.

I loved the way she started by sharing her intellectual biography in a way that wasn’t about maximizing cultural capital: e.g., the “my many brilliant accomplishments!” model that you hear at many academic events (is vanity simply inverted insecurity?). Instead, she was explicit about filling in the gaps in her own CV to show what a circuitous route we often take to our jobs.

Is it easy? Of course not. She talked about the very real struggles of being a new PhD, filled with uncertainty about her job prospects but pretty certain that a standard academic position sounded like a deadline-infested drag. Like most people straight out of grad school, she said that she struggled at first. She talked about needing to write her book’s introduction in a two hour window at a Starbucks (which was as long as she could be away from her newborn twins), and about being a first generation college student in Iowa before landing in prestige machines like Yale and the Getty.

It’s important to hear stories like this. Relatively few people go from a PhD program to an amazing postdoc or an attractive TT job nowadays–it was always difficult but feels particularly tricky in 2022. Most people are like me: in the 1990s I worked in publishing in multiple positions, taught at different levels including a high school, worked in a museum, and even dabbled in journalism (well, I was an unpaid “contributing writer” for a NY magazine, which at the time seemed like it might be a career path). You can see these elements on my own CV, but not the fact that I also worked as a night janitor in a bank, a UAW organizer, an undergrad counselor, among other gigs—all before I took an assistant professorship (and all while trying to write and publish on the sly!).

Back then I was convinced that success was only possible if I landed an assistant prof gig, but reality is much more complex than such Manichean scenarios.

The upshot for me: maybe don’t put all your emotional eggs in one professional basket. There are so many ways to use the skills we gain in American Studies, and many of them (in my experience) offer as much or even more joy, community, and dignity than the often elusive TT line (and yes, it was elusive even in 1995!). Instead of having the narrow mindset of “I must grab any TT job that I can get, even if it’s in place that irritates me on every level,” think about what really matters to you.

This is why I appreciated it when Dr. Peabody talked about the importance of not letting your career be your number one priority in your life (to the extent that your circumstances allow. Economics are always weighing heavily on this matter). I get it. After spending 6+ years in grad school, it can be very hard to say “maybe I’ll end up teaching at a nice college or maybe I’ll do something else that is just as great.” But I recommend that flexible mindset when you embark on grad education in the humanities and social sciences. Giving yourself choices is the first step to actually having choices.

Obviously I found her talk very empowering—and was grateful to Annie Maxfield and the Texas Career Engagement office for making it happen!

Learning and Unlearning: Education in Flux

By Amanda Tovar, PhD Student in American Studies, UT-Austin

As a Latina who used to hate herself, Gloria Anzaldúa’s work challenged me to love myself. Additionally, her work propelled my journey in higher education. Her text Borderlands provided me the confidence I needed to see value in my lived experience to the point that it made its way into my work. But what does that mean in 2022 when valid critiques of her work have come to light? What does it mean that I read and used her work for so long but did not realize the problematics of her work?

For clarity, Gloria Anzaldúa’s work has come under fire recently for perpetuating Indigenous erasure via cultural appropriation. Likewise, her concept of mestiza consciousness stems from José Vasconcelos’ concept of raza cósmica (cosmic race), the result of mestizaje. La raza cósmica and mestizaje are both extremely racist and essentially call for the muting of Indigenous and Blackness for the sake of “one” “cosmic” race. There is no justification for using this, at all, in any way shape or form.

Admittedly and ashamedly, I wrote an introduction for an academic journal where I stated that Anzaldúa’s work “nourished my mestiza soul,” and not only is that CRINGEY for me now, but it is heartbreaking. Heartbreaking because I was so deep in my own world that I did not consider the real- life implications of a text that’s main theoretical concept upholds and perpetuates white supremacy.

For some time, I have wanted to hide my head in the sand and pretend that my previous writing and work did not exist, but that would be cowardly. Instead, I want to own the hurtful words I espoused and upheld and hold myself accountable for the sake of my own personal growth—academically and personally. Does this excuse me of my wrong doings? Absolutely not, but I want to be very intentional and honest with myself and others moving forward in my academic journey.

Being oblivious to the problematics of certain aspects of texts that I once regarded highly caused real harm to which I acknowledge fully. For some time, even, I “cancelled” myself to the extent of not producing or sharing my work with anyone outside of immediate professors because I felt immense shame in being someone who perpetuated harm. And then I came across Adrienne maree brown’s We Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative Justice and it greatly shifted my perspective.

brown likens us (people) to mushrooms, all connected underneath the surface and states that the same is true about conflict and harm (brown, 8). She states that a toxic substance in our interconnectedness is supremacy, that is has been invisible to those who benefit from it and is “desirable” by those suffering from it—and that was true in my case and the case of many colonized brown folks (brown, 8). My proximity to whiteness bred problematic ideologies that allowed me to uphold mestizaje and mestiza consciousness as something to be celebrated. And again, nothing excuses it, but I am holding myself accountable and unlearning what I once knew.

While I can dig and dig and dig and expose the crux that lies beneath the metaphorical soil that is my lived experience, it is not enough. brown writes that “we need to flood the entire system with life- affirming principles and practices, to clear the channels between us of the toxicity of supremacy, to heal from the harms of a legacy of devaluing some lives and needs in order to indulge others” and I fully agree (brown, 8). We need to unlearn behaviors and information that we have been immersed in and begin anew. As brown suggests, I will tell people I have hurt people, I will do the work, I will learn new things, and I recognize that it is not too late (brown, 76). My education—personal, academic, and otherwise—is in constant flux.

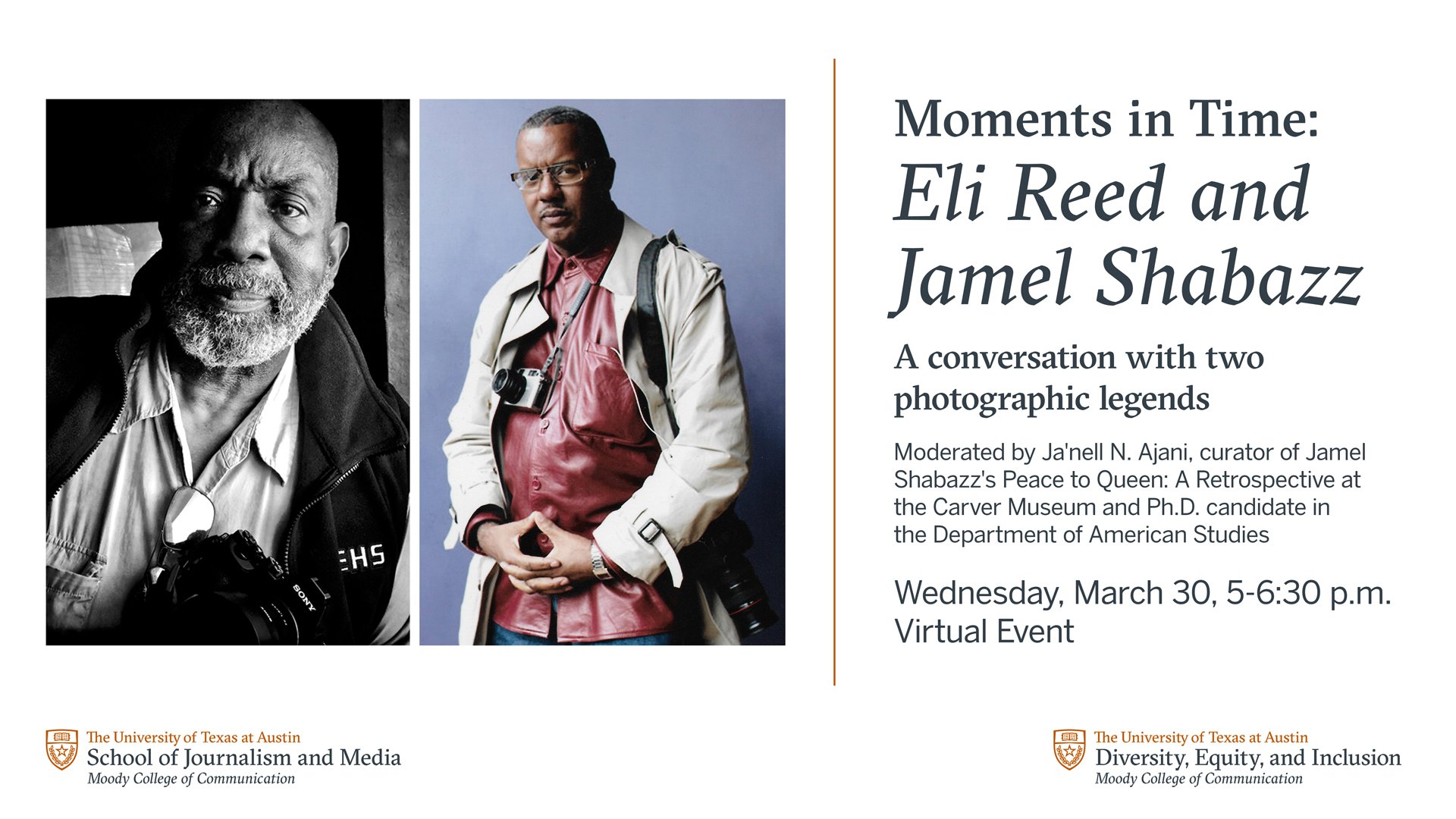

Moments in Time: Eli Reed and Jamel Shabazz

American Studies PhD student Ja’Nell N. Ajani will be moderating this conversation! Register here.

Experimental American Studies and the Elements of Marfa

photos + essay by randy lewis, chair and prof in the Department of American Studies, about one of the many exciting things going in UT American Studies: think of it as an invitation to create similar projects on other topics and in other places…

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Do you ever think about the endless intricacies of the periodic table? You do? Well, not me!

Yet lately I’ve been wondering if humanities scholars have something worth saying about helium, nickel, copper, lithium and the rest of the elemental stuff we haven’t investigated since high school chem? Can we write something vivid and meaningful about the elements that emphasizes the power of culture, history, and identity in areas far from our usual expertise? My answer is firm and clear: definitely maybe!

At least that’s what I was half-seriously thinking when I joined a new collaborative writing project on the elements dreamed into existence by anthropologists Marina Peterson (UT Anthro) and Gretchen Bakke (Humboldt University, Berlin). In the past few months the dozen or so members of the project have each selected a single element to write about, with others expected to join in the months ahead. Then with initial funding from a Texas Global Faculty Seed Grant, we met in Marfa for two days of fieldwork, planning, and workshopping, with the ultimate goal of producing a short essay on every element in the periodic table. Imagine 118 tiny books on the cultural lives of the elements and you’ll get the idea.

On the sublime road from Marfa to Fort Davis, home of the McDonald Observatory (all photos by author)

Well known for their research on various kinds of infrastructure and atmosphere, Marina and Gretchen planned out a judicious blend of structure and chaos for the weekend (an overly structured event is deadening; pure chaos is disorienting). The long stretch of communal time allowed for something that’s rare on campus during the Zoom age: we got to know each other a little bit. Marina rented a small architectural gem of a house where we met up with a pile of books, electronic gear, basic bookmaking equipment, and posters of the periodic table. My first thought is wow: this is cool but what the heck are we doing?

Some of the books Dr. Marina Peterson had brought for our collective inspiration

And that’s not a bad question to ask yourself at the beginning of any research project. In fact, this positive perplexity is why my favorite work happens in situ and especially in places like Marfa. As a grad student in the early 1990s, my first trip to Marfa hit me like a meteor of possibility. Back then Austin was much more shaggy than cosmopolitan, very far from the slick global brand that it is today—so much so that Marfa seemed like Soho in the desert on one particular weekend in 1991 when I showed up in my little Ford pickup. Claes Oldenburg was strolling around the grounds of the Chinati Foundation, Gus Van Sant’s short films were projected inside an empty swimming pool, random bagpipers wailed like angry cats in the dark, and a smattering of local ranchers stood around a bonfire gripping Shiner Bocks and wondering what to make of all the wildly dressed art students. Everyone was mingling at a free annual party held by the minimalist sculptor Donald Judd, who had been remaking the town since relocating from Manhattan in the 1970s.

This wonderful weekend planted a seed in my mind that Marfa was a special place for creative experimentation, while also giving me hope for a kind of lone star transformation that often seems out of reach. Because my own family has been in the state since the 1830s, mostly not transforming, not finding an easier way forward (for instance, this is my wonderful but excessively hard-working aunt), I am incredibly invested in ways that Texas can change for the better—and watching my sleepy slacker Austin becoming a glitzy Technopolis with an Apple campus, million dollar condos, and a massive Tesla factory is not really what I had in mind.

My own aspirations are closer to what I found in Presidio county ever since that initial trip in 1991. If dusty little Marfa can go from a sleepy ranch town to a global art mecca (not without its drawbacks, to be sure), then perhaps our state can evolve into something other than heat-baked sprawl, CRT-phobic suburbs, struggling small towns, and an ever-widening interstate system that eventually swallows us whole.

Happily, the elements project has a perfect crew for imagining something better, if only in a preliminary and exploratory way. Some familiar faces are in the room in our little Marfa HQ-–Lindsey Freeman (Simon Fraser U) is one of the most perceptive and graceful writers now in academia. Craig Campbell was there in his old Mazda pickup with Queen Elizabeth waving ironically from the window: if you are doing something at the nexus of art and anthropology, or anything that is just plain novel, cool, and brilliant, Craig is probably in the mix (as he was for the Carceral Edgelands Project earlier this year, and the Ex Situ Collective, which has met for similar projects in Austin, Windsor, Athens, and here in Marfa in 2014 for which we had to create work while in transit). Fusing art and scholarship into a collaborative and often accelerated process is always a revelation, and these academic experimenters are my core peeps, intellectually and temperamentally speaking, as much as American Studies.

Dr. Craig Campbell, UT Anthro, with his regal co-pilot

Looking across Marfa’s main drag with some ironic commentary for academics who love to talk!

So what was the experience like? I rolled into town, dusty and tired in the late afternoon. Within 30 minutes, I wandered into the coolest shop ever, run by a wonderful guy who I interviewed for my film on Prada Marfa last fall, whose interior designer partner told me mind blowing stories about the contemporary art scene in Mexico City; then I walked into a photo shoot for a catalog where they let me sit inside a 1953 Studebaker Commander; and was told that Lady Gaga was in town for a Dom Perignon shoot (alas, untrue!), while a friend was emailing me that Grimes and Chelsea Manning are dating back in ATX. That’s how Marfa is. If I walked around a corner and bigfoot was playing banjo with Miranda July and Harvey Keitel with Beyoncé at the conductor's podium, I would have been like “sure… that makes sense.”

Marfa is heaven for people who love old trucks and cars (as the author does!). The elements (in another sense) weigh heavily on machines, houses, and people in West Texas.

For the next 48 hours I worked alongside various participants, watched a dirt devil rip off a big section of a roof, and prayed for the wind to die down because the swirling ragweed was hitting me like a thousand hangovers. At night we donned six layers of clothing and drove to the McDonald Observatory, which is one of the greatest appendages of the UT world. I peered through telescopes and saw Orion’s Belt, lunar close ups, and hazy nebulae, while the astronomers nerded out on our dopey questions. So many brilliant minds in the Davis mountains figuring out the universe—astronomers have to have the souls of poets, right? Perhaps the question for our gang is the obverse: do poets have the souls of astronomers?

An oblique form of inspiration bubbles up as we approach helium, hydrogen, lithium, and the rest of the cosmic stew in our own cult studies way, hoping to create micro books on individual elements. Mine is dedicated to lithium, about which I knew nothing last year. Now I is expert! (I’m riffing off an old engineering joke). For weeks I've been reading about its applications: the batteries of Elon Musk, the mental health of Brittney Spears, the music of Kurt Cobain. It’s in fireworks, pacemakers, lubricants, hydrogen bombs—everything seems to need it nowadays.

One surprise about driving from Marfa to ATX along the border is the extraordinary beauty of the Pecos Canyon Bridge, with hundreds of wild goats far in the distance. If we blew up the photo, you’d see them on the right side of the river.

The Elements crew took a field trip to Shafter, a nearby ghost town now where 2000 miners are buried. Almost no one lives there today, but we met a happy couple who had been residents for 30 years.

We kicked around another element in the morning, driving an hour south to take notes around a dead silver mine in Shafter, Texas, almost on the border. Megan Gette, a talented graduate student from anthropology with a creative writing background, used hydrophones and contact mics to record the ghostly sounds of metal and dirt. She let me listen to her headphones and I was shocked: a metal fence sounds like a didgeridoo when you tap it softly.

Group work is messy by necessity. Back in town we gently argue for an hour about what to call the publications. Over the course of two days we plan, write, design, cut and fold dozens of prototypes (one participant says it’s a bit like elementary school). It’s not all forward progress and it may not yield a consistent neoliberal knowledge-nugget with quantifiable “impact factor,” and yet I look around the room and see my favorite model of academic life. Anthropologists, humanists, sociologists, and poets. Lots of movement, lots of dialogue, lots of snacking. A lot of group work, DIY fashioning, and a handmade product that is about the creation of new forms of knowledge.

Co-organizer Gretchen Bakke from Berlin, along with Megan Gette and Monti Sigg from Austin

Not surprisingly, I start thinking of it as “artisanal academia.” Chaos and brilliance simmering on the stove together: it’s exhausting but convivial work that will yield an atypical academic “product.” Given the overproduction of standard journal articles that often go unread or quickly obsolete, I’m fascinated by our embrace of the ephemeral: we are in the realm of experimentation, collaboration, and innovation in form (which often happens when artists are injected into academic settings, or when you work with academics who are also artists/poets).

Pondering the elements!

The trailer park that never happened, near the ghost town of Shafter, which has an amazing local history center with fascinating information on display. Only a few people live nearby where once thousands lived and died in pursuit of silver (atomic number 47).

The reality of Marfa is a profound visual inconsistency in the built environment. It’s a rapidly gentrifying town where a NY investment banker might own a million dollar third home that they almost never visit—and it’s often right across from a house like the one above in the heart of town. Hyper-modern homes with lap pools and fragile leftovers are juxtaposed on Marfa’s streets, more so than anywhere I’ve ever been in the US. See Kathleen Shafer’s book on Marfa for more on the town’s history.

So that’s what I did for the first few days of Spring Break. People hear the word Marfa and they probably think minimalist art vacation or something—and it was in the sense of being out of the normal traffic and hustle of the violet crown.

Near the abandoned silver mine of Shafter, searching for inspiration and/or a cell signal

But it’s also not nothing to drive 1000 miles in four days and take part in an ambitious collective experience, sustained mostly by the quality of the minds and the idealism of the people around you. I was exhausted when I rolled back into ATX, immediately sprinting to catch a bullet train of bureaucratic obligation. Squeezing back into my little work silo to manipulate symbols that flicker across multiple screens with endless continuity, simultaneously dulled and jittery, social but alone, I’m already thinking about the wildness and possibility in the elements of Marfa.

The great sociologist Lindsey Freeman, a Tennessean now in Vancouver, and the author of This Atom Bomb in Me and Longing for the Bomb

The author looking ready for the wind apocalypse in Shafter, with photographer Monti Sigg

The importance of snacks and wine to intellectual work can never be underestimated!

Traveling Back in Time to “Weird Austin:” Daniel Johnston “I Live My Broken Dreams

by Holly Genovese

Photos also by Holly Genovese

I’m not from Austin, or Texas, and before moving here in 2018 to study I had visited once, for 24 hours. I knew Austin had a reputation for being cool, but I couldn’t have told you why. I’m from the East Coast, and one thing I’ve realized since moving to Texas is that the East Coast thinks a lot of itself. We learn very little about anything west of the Mississippi and I only realized that when I left. I’m not from New York, not even close, but the “View of the World from 9th Avenue” cover of the New Yorker feels very relevant.

I didn’t know Austin used to be weird or that the city really loves movies or that so many famous people live here. I had no idea. I quickly realized that the “weird” identity of the city had all but disappeared decades before I arrived. Sure, there were the stickers. But it was difficult for me, moving to the city in 2018, to even understand what it was that Austin had lost. I knew it as a booming tech city, increasingly overpriced. I knew that it was incredibly white and getting whiter all the time. I knew that more and more tech moguls and celebrities were moving here. But much of the cool stuff had already been lost. I missed the last gasps of Austin as a hub for weirdos and creatives and moved here when it was already really hard to survive as a weirdo or creative (or a student, like me). To me, Houston, with its food scene and museums and Parts Unknown episode seemed like a real weird, creative city.

Even though I got here too late, there were still closures that hurt. The loss of our two video stores, Vulcan Video and I Luv Video, hit me hard. And the pandemic closure of Spiderhouse Cafe, which I didn’t learn about for months. And I’ve slowly discovered the places that do make Austin special–AFS, for one. Austin City Limits. The many independent bookstores, including Bookwoman, which has been around for 40ish years. But what really showed me what Austin once was, and never could be again, was the Daniel Johnston exhibition at The Contemporary ATX. The exhibit focuses on Johnston’s legacy–both his connection to Austin as well as his artwork and music. Johnston was the quintessential Austin weirdo-handing out mixtapes with hand drawn art at the Mcdonalds on Campus (there was a McDonalds on campus?). He gave off tremendously low-fi vibes in the early 90s, even as he painted a famous mural and Kurt Cobain wore a shirt with his artwork on it.

The exhibition shows the evolution of his work, as well as his music, and even includes a recreation of his workspace. A piano surrounded by toys and comics and funky objects. His work asked big philosophical questions through comic inspired art (Johnston loved Marvel).

I don’t why, but seeing Johnston’s art, seeing what Johnston was able to create in Austin, finally showed me what was lost when Austin stopped being weird. The Sound Exchange, where Johnston painted his famous mural, has been closed for 20 years. Nearly a decade before that, it was voted the “Best Place to Buy into the Underground” by the Austin Chronicle. For many new Austinites, the Underground has never existed in Austin. But the Contemporary’s exhibit on Johnston gave me a way of seeing an Austin that, for me, would never exist.

You have four more days to see “Daniel Johnston: I Live My Broken Dreams” and it’s absolutely worth braving the SXSW crowds for the chance to travel back in time to cool, weird, Austin.

Contemporary Art in San Antonio 2022-A quick look from UT Am Studies

“As an American Studies department based in Austin, we are lucky to have San Antonio just an hour away. On my way back from a two day writing workshop in West Texas with 15 scholars from all over, and after pausing at Judge Roy Bean’s homestead in Langtry, I stopped to see contemporary art shows at the city’s main museum as well as the small but always interesting ARTPACE. The shows were so good that I thought I’d make a 4 minute video that would serve as a introduction to our students and anyone else who is curious. If you haven’t been to these places, or if you don’t know Wendy Red Star, now is a great time to head down I-35.” — Randy Lewis, Chair, Dept of American Studies

Third Thursday Weds March 23rd

Come learn about the Annual Sequels Conference as well as the E3W Review of Books, which many UT AMS students have worked on!

UT AMS Alum Dr Christine Capetola to Give Talk Today

Contact Dr. Capetola for access information,